The 3 guidelines when moving with pain feels scary

It’s OK to move with pain

One of the first steps in the pain rehabilitation process is establishing that it’s ok to move while in pain. Some people understand this intuitively as they’ve been in pain for years and continue to live their lives, albeit modified in their activities and movements. Others tend to avoid any movement around the painful body part until it no longer hurts.

But there obviously have to be caveats to moving with pain because pain exists for a reason. Pain is an alarm signal – it’s trying to protect us from harm or further harm. So it makes sense that the number one question I get asked is, “How do I know when moving with pain is causing harm?” Basically, when should you listen to your alarm and change your behavior and when is it safe to keep going?

The crux of the question is the conflict between wanting to make progress in rehab (or continue with desired activities in life) and not wanting to create more damage to the painful body part. There are three guidelines to help when this comes up – and two prerequisites to understanding the guidelines.

Two Key Points about pain

Pre-req #1: Having pain never ONLY directly correlates with tissue damage.

Pain is a huge and complex system intertwined with various other systems in the body. When you feel pain, there are always many, many systems at play. This is one reason why your knee might hurt one day and not the next even though you’re seemingly performing the same movement. If you have a history of disc herniation and your back hurts, your back is never the only contributor to your pain experience.

Pre-req #2: Pain is an alarm signal.

It’s the precursor to things going wrong, not the news alert that something has gone wrong. This is a big distinction. When you break your arm, it hurts because your body is trying to tell you to leave it alone so that it can heal. If you continue to use it, it won’t heal and it’s a threat to your survival. If you place your finger on a hot stove for one second, you will feel pain, but you likely won’t experience a burn yet. You feel pain as an alarm to change your behavior, ie take your finger off the stove, so that you don’t cause harm. The sensitivity of the alarm is highly variable from person to person and from day to day within each person. This means there’s wiggle room between the time you receive an alarm signal, and the time to actual injury. This is why it’s often ok to move with pain. There’s often a lot of wiggle room.

Each of the above points is a HUGE pain concept, so if you still have questions, that’s ok. Keep them in mind and stay tuned for future posts were I will discuss each in more depth. Let’s review the three guidelines.

The 3 Guidelines for moving with pain

#1 The Pain Scale

The pain scale is a simple tool to help someone gauge their pain at any given moment. The scale is 0-10 where 0 is no pain at all and 10 is excruciating. The general rule of thumb is not to continue the exercise or activity if your pain feels higher than 5. At a 5, there should still be no facial expressions of wincing, holding the breath, or muscle tension to brace against the pain. I often find that people are initially nervous about moving with pain. Once I ask them to rate it on the pain scale and they discover it’s actually at a 1 or 2, their own realization that the level of pain is lower than what their reaction induced reduces their fear in the situation and encourages them to keep going. On the flip side, if your pain is at a 4 or 5, which lies within the threshold of this rule, but you’re incredibly nervous and fearful of hurting yourself, then continuing will do more harm than good. Your nervous system is aroused into a more sympathetic state and your body feels threatened and unsafe. In a rehabilitation setting, this is not the environment we want to cultivate.

Note: Six on the pain scale is not the number at which, all of a sudden, your tissues will in fact get damaged while at 5 they’re ok. Five is, in general, the level of pain people can tolerate before changing their behavior during the movement – as I mentioned above: facial wincing, breath holding, bracing. (You can read more about pain tolerance here.) These behavior changes signal to the nervous system that you're unsafe and the movement you’re doing is unsafe (whether that’s objectively true at the level of your tissues is irrelevant). These signals further wire your brain’s association of that movement with pain, when in fact, rehab exercises are trying to disassociate pain with certain movements.

#2 The 24-48 Hour Rule

Nudging the boundaries of pain – or “poking the bear” as physical therapist Greg Lehman would say – can sometimes cause a reaction. The reaction might be swelling, increased tenderness, soreness, general increase in pain symptoms, or other effects of peripheral inflammation. However, if the reaction dies down after 24 hours (and for some people a window up to 48 hours is more appropriate), your body did what it was supposed to do. It sensed a stressor, it heightened your immune system response to address it, and the acute inflammatory response dissipated in a timely manner. This is what is supposed to happen. When you exercise intensely, your body undergoes the same acute inflammatory process of sensing the stress, heightening your immune system activity to heal the disruption that exercise causes, and the end result is that you're more prepared to handle the stress the next time it comes. In regards to pain, the acute inflammatory response, when it functions well, will increase your resiliency and slowly start to move your boundaries further and further away.

If the symptoms last longer than 24-48 hours, that’s excellent data for you to collect – the movement/activity at that point in time caused a disruption large enough that your body needed more than the normal time to come back to homeostasis. It doesn't mean you damaged anything. So why the 48 hour cut off? Beyond 48 hours might mean your inflammatory system is dysregulated. It also means there's considerable interruption to your quality of life. Now you know that next time, you lessen the load which could be: less weight, reps, total volume of physical activity, and/or evaluation of your current algorithm . . .

#3 The Algorithm

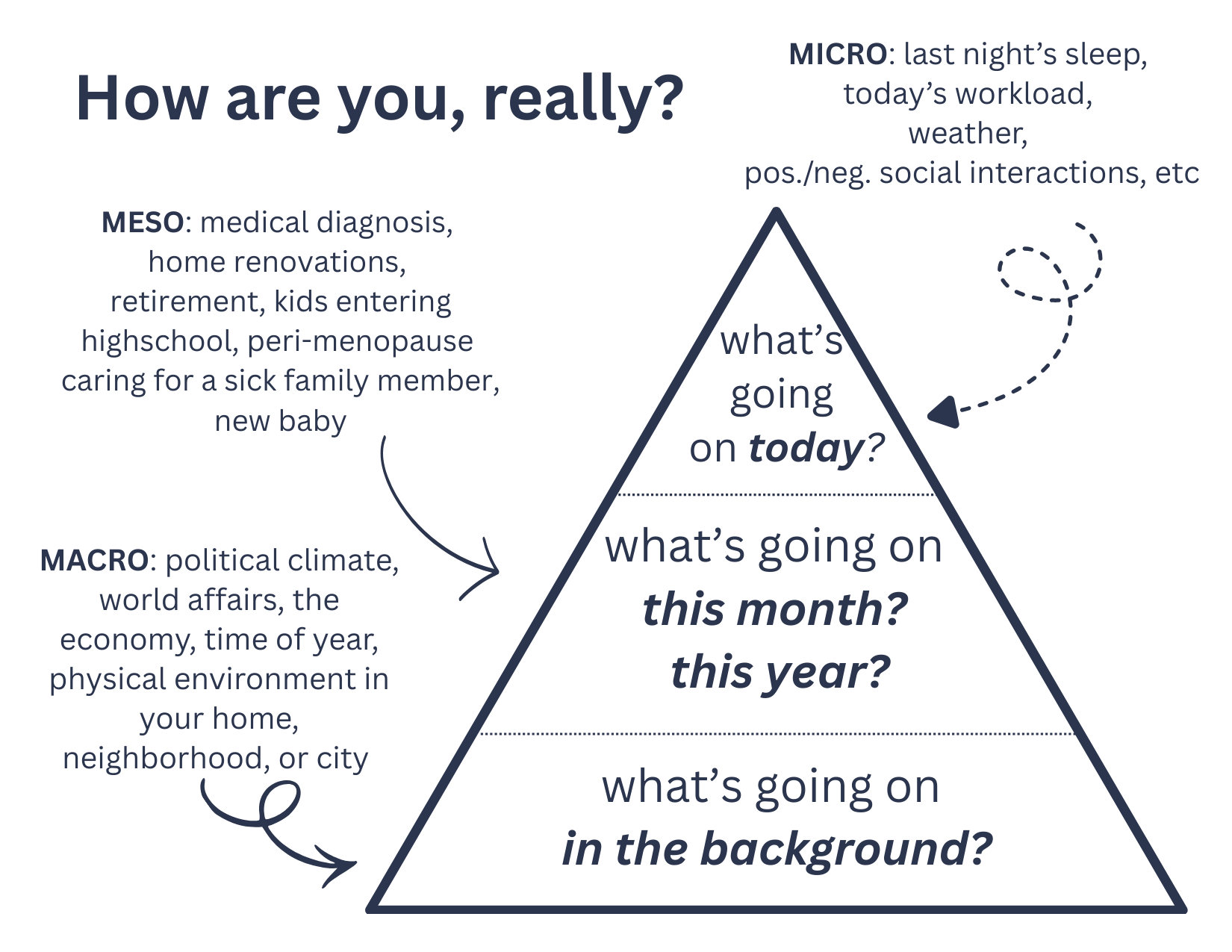

I don’t know if this happens to anyone else, but when someone asks me how I’m doing, I’m like . . . it depends . . . how am I doing right this second? Or this week? Or this month? Or this year? Also in which sector? Work? Family? Friends? Physically? Personal development? Because those are all different answers. This is how how I feel trying to answer that question . . .

Our life, at any given moment, can be seen as an ever-changing algorithm. Not taking it into account during a decision to push through or pull back when moving with pain is the biggest oversight one can make. If you just finished hosting Thanksgiving for 15 people, are traveling for Christmas, trying to sell your house, and dealing with what might be some gastrointestinal issues, that is all part of the algorithm that’s present in the moment that you’re deciding whether or not to go on a long walk because you’re not sure if it will flare your outer hip pain. What’s also in that algorithm? Well, it’s possible you didn’t have time to eat much yesterday so your glycogen stores today are depleted. But you also slept like a baby, and later tonight you have an outing with friends you’ve been looking forward to all week. You also got some extra snuggle time with your dog this morning while reading the news and you’re having a pretty good day so far. This all part of your algorithm, and one that I encourage everyone to check in with when making decisions about continuing to move through pain (even if it’s below a 5 on the pain scale).

Here’s a list of many of the things affecting your algorithm, and therefore the sensitivity of your alarm signal at any given moment.

The algorithm image is what resonates with my brain the most. But you can also think of it like a scale. One one side of the scale are things that might be taxing on your system and on the other side of the scale are things that might alleviate stress on your system. The scale is constantly moving back and forth, every moment. Which side is heavier at the moment you are making a decision about moving with pain?

At the end of the day, this concept answers the question, “How are you doing, really?” and encompasses everything that affects our brain’s decision to send us a pain signal. A third way of picturing it is like three simultaneous timelines of life - micro (today), meso (this week/month or year), and macro (year or decade or things ongoing in the background). Imagine someone asks you how you’re doing and really wants to hear the full, unedited version.

My Hope

Guideline #3, your algorithm, subconciously influences your answer to #1 (where you are on the pain scale) and the outcome of #2 (the 24-48 hour after effect of pushing through pain). There's no separating components of the pain experience. Also, these guidelines aren't meant to be followed in the exact order I wrote about them. Depending on what you're doing or where you are in the decision process to go ahead with an activity, these guidelines will change order and change in how much they influence your decision. And while initially, assessing your algorithm may seem like a lot of work -- it does require a minimum ability to be aware of one’s own state of being -- my hope is that in conjunction with the first two guidelines, and a reasonable understanding of the prerequisites, you’re on your way to becoming more heavily armed to make the best decisions for your body in moments of uncertainty in moving with pain. Will you get it wrong sometimes? Absolutely. You will sometimes do too much and experience a flare up. And in that case, I invite you to curiously ask yourself what went wrong and see it plainly as data to help you in future decision making. But using this framework, you're more likely to keep actual tissue injury or a severe flare up at bay while you continue your rehab journey and/or the activities in life you love to do.

keep moving,

alia